Originally Published by Sociological Studies Research University of Sheffield https://socstudiesresearch.com/2021/10/26/beyond-gender-wars-and-institutional-panics-recognising-gender-diversity-in-uk-higher-education/

By Sally Hines

According to the UK’s media, academia is currently plagued by ‘silencing’, ‘no-platforming’, and ‘cancel culture’ amidst the Nation’s ‘gender wars’. Over the last year, barely a week has gone by without a broadsheet newspaper article, radio discussion programme, or TV report suggesting that UK Higher Education (HE) has reached crisis point in what has become to be articulated as a ‘culture war’. Indeed, as I write, two UK universities are embroiled in controversies around student protest and issues of free speech.

The ‘Gender Wars’

Between 2000 and 2004 I worked on my PhD on trans identities and communities. During this time, very little cultural commentary was given to the experiences of trans or non-binary people. My topic was viewed by most as niche and a little eccentric. In 2004 Nadia Almada won ‘Big Brother’, marking what I have written about as a ‘cultural turn to trans’ (Hines, 2007). The same year, the UK Gender Recognition Act (GRA) came into law, enabling trans people to change their birth certificates and other official documents to their acquired gender. While, over the next decade, the UK media (for good but more often bad) couldn’t get enough of trans people, the legal and policy shifts enacted by the GRA passed with very little attention in cultural or political arenas. Such disinterest was not the case, however, when, 10 years later, amendments to the GRA were proposed. Those most exercised by what were in effect minimal administrative changes to a law protecting the rights of a small minority group, organised under the guise of ‘gender critical feminism’. Gender ‘ideology’, it was argued, was outstripping the rights of (cis) women as a ‘sex class’.

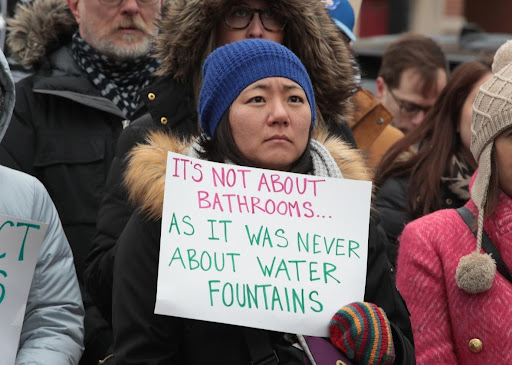

Despite evidence that most people in the UK are supportive of trans rights (YouGov, 2020), the ‘gender critical’ voice has been amplified through the support of broadsheet journalists and cultural commentators. Though trans hostility has always been evident within sections of second-wave western feminism (see Serano, 2007; 2013), in addition to the supportive commentary in traditional media, social media, and particularly Twitter, has accelerated the anti-trans feminist narrative to levels unprecedented in their previous incarnations circa the ‘sex wars’ of the 1980s. Changes to the GRA that were simply intended to make a legal process less bureaucratic for those seeking recognition have been interpolated into concerns around cis women’s safety in public spaces. The unwillingness of gender critical feminists to explore the fluidity of the categories of sex and gender – and their unpredictable relationship – fixes gender to a simplistic model of biological sex that refuses to recognise trans women as women. This view then enables them to position trans women as potential male sexual predators. The absence of any evidence to justify such fears, has done little to halt a prevailing moral panic around the access of trans women to ‘single sex spaces’ such as toilets, prisons and domestic violence services, a right that is set in law (Equality Act, 2019). This not only discursively excludes trans women from the category woman, but also aligns trans women with violence against women (Phipps, 2016). As work by scholars such Dara Blumenthal (2014), and Charlotte Jones and Jen Slater (2020) remind us, access to public toilets is a basic entry point to public life and participation in civic society. Moreover, as critical race scholars have long pointed out, toilet segregation, alongside other public activities such as drinking water from a fountain or riding a bus, were instrumental to the Jim Crow laws that upheld white power and violence in most parts of the American South until challenges brought by the Civil Rights movement of the 1960s. Policing identities – or boundary making – has a long and troubled history.

(Photo by Scott Olson/Getty Images)

Beyond the ‘bathroom problem’, the rights of gender diverse people have been contested across several arenas by UK gender critical feminist organisations. Most notably are proposed restrictions to healthcare and challenges to the Equality Act, as evidenced in the ‘Declaration on Women’s Sex-based Rights’ (2021) authored by Women’s Human Rights Campaign (WHRC).

It is, then, within this wider political landscape and policy context that HE has entered the affray. Of long-standing concern to gender diverse students, staff and their allies has been the issue of external speakers on campus who are well known for their gender critical views and/or involvement in organisations that campaign for a roll-back of trans rights. More recently, however, the focus has turned inwards as questions are raised about the impact on student welfare of high-profile gender critical senior academics in a number of HE institutions.

Duty of Care and the Limits of Free Speech

In recent years, feminist politics around trans have affected much broader discussions about HE culture and its duty of care for trans and non-binary students and staff. Here, notions of ‘safety’, ‘free speech’ and ‘censorship’ are counter-posed in debates about ‘no-platforming. The term ‘no platform’ can be traced back to social movement politics of the 1970s when left-affiliated organisations sought to prevent far-right groups, such as ‘The National Front’, from speaking and demonstrating in public spaces. The National Union of Students (NUS) similarly developed its no-platform policy in 1974 to prevent far-right groups demonstrating on campuses.

Within feminist politics around trans, the term ‘no-platforming’ has become commonplace. In 2011, the NUS Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual and Transgender Conference (GLBT) voted to apply the NUS no platform policy to feminist writer and activist Julie Bindel, and, over the last decade, several other gender critical speakers have been included in NUS no-platforming policy. Such decisions are upheld on grounds of protecting students from emotional harm in line with NUS ‘safe space’ strategy. Subsequently, those concerned use their media access to denounce these decisions, arguing that they have been censored, bullied, and had their right to ‘free speech’ violated, resulting in more media coverage, which, in turn, ironically, further proliferates their claims of silencing. No-platforming in these instances is frequently pitted against the democratic practice of ‘debate’. Guardian and New Statesman writer Sarah Ditum thus states: ‘A tool that was once intended to protect democracy from undemocratic movements has become a weapon used by the undemocratic against democracy’ (Ditum, 2014). Yet, as Sara Ahmed’s (2012) work shows, it is those who have the greatest levels of cultural and material capital who have the highest access to public platforms. Still, the language of censorship is invoked; an invocation that obscures levels of structural power (Phipps, 2016, Hines, 2017) and pays little attention to issues of cultural capital and institutional power inhabited by the high profile feminist academics and journalists who populate anti-trans discourse.

As these issues intensify in academia, the question has turned to issues of free speech in relation to members of staff with a high public profile for views deemed harmful by gender diverse students, staff members and their allies. Many column inches, TV coverage and radio airtime has thus been given in recent months to those who claim that their views on the importance of biological sex are being silenced. Said academics present themselves as ‘reasonable’ in contrast to the ‘snowflake’ student population of contemporary times. Here the onus is firmly placed on the student to listen – University life is, they are firmly told, all about listening to complex ideas. Listen and learn.

Such demands on the student, though, not only reflect an outdated institutional paternalism, but fail in their acknowledgment of relationships of power, and institutional commitment to a duty of care for students of marginalised gender communities. Moreover, this underscores a huge experiential gap. As trans and non-binary people have long pointed out, what may be an issue of academic inquiry into the relationship between sex and gender for a cis academic with high levels of economic, social, and cultural capital, is a matter of everyday survival for members of a marginalised group who experience reduced physical and mental health, disproportionally face poverty and unemployment, and are impacted by high levels of stigma, discrimination, harassment, abuse, and violence (Stonewall, 2020).

Grace Lavery’s (2021) recent piece on events at Sussex, makes a crucial distinction between ‘academic freedom’ and ‘free speech’. While free speech is a nebulous principle, academic freedom is tightly defined to protect the rights of academics to research within their areas of expertise. Further as Lavery points out through drawing on the latest work of Joan Scott, free speech is often at odds with academic freedom:

In recent years, academic freedom has been under threat from the far right, who have consciously attempted to replace the academic’s freedom to research with a broader right to say what one likes. This then serves to undermine faith in the public university, turning scholarly judgement into mere opinion-generating punditry and serving the policy goals of those who seek to defund public education altogether.

It is in the interest of the University itself, then, to develop a critique of the current sloppy usage of ‘free speech’. Moreover, putting to one side the very fuzzy legal line between free speech and hate speech, if material disparities and experiences of discrimination are to be taken seriously, the focus must turn to those members of the student population (and precarious members of staff) who feel detrimentally impacted by the words they are forced to hear. This, though, demands a move away from the right to speak and a refocus on the responsibility to listen. Since the last five years of ‘debate’ have shown that this is not going to occur through a change of heart, we must turn to the building of robust equalities, diversity and inclusion initiatives pertaining to gender diversity.

Developing Equality, Diversity, and Inclusion Policy on Gender Diversity.

The importance of reflecting on whose voice matters in education has come to the fore as part of the project to decolonise the curriculum. The decolonising movement emerged to address discrepancies of rates of attainment, progression and continuation of students from black and minority ethnic communities, compared to their white peers, and has developed to reflect on the positionality of the Cannon more broadly. As Elisabeth Charles (2019) asks about the position of students from marginalised communities:

What happens when they [students] become aware of a lack of visibility of plural voices, or of people like them as having contributed to the subject, or who might have a different narrative to the ‘story’ being told? What happens to the student when they do not hear their voice at all, or when they do, it is glossed over or framed as a negative? The message that is being communicated is then that you don’t belong, or that people like you have made no contribution to this subject area. More importantly, if you as the non-expert want to start a discussion about this lack of inclusivity, how do you phrase this so that it is seen as contributing to a discussion rather than disrupting the orderly flow of the class? Does the student have the confidence to start being critical on a topic they are just starting to understand; and how will it be perceived by the academic and other students? […] In any case, why should the task of diversifying the voices included in the curricula rest on the shoulders of students who are marginalized or other?

Moves to decolonise the curriculum have at their heart epistemological questions of (in)equality and are guided by a commitment to social justice. In the institutions that have made the most progress in their decolonising projects, the BAME Student Union community has been a key consultant and evaluator, showing the importance of transforming epistemological values and disrupting traditional relationships of power.

I would like to see similar initiatives being developed in HE to address the institutionalisation of transphobia. This would, importantly, entail a discursive shift from anti-trans rhetoric as ‘opinion’ or personal viewpoint and enable the recognition of structures of power. This would also mean that trans and non-binary students were taken seriously as experts with the authority to question and challenge the pedological practices that they experience as discriminatory. It is also important that a pro-active gender diverse educational culture and curriculum be incorporated into HE’s duty of care. Rather than a minority-focused initiative, gender diversity education is important for all students and staff members. Indeed, one of the key findings of our ESRC project ‘Living Gender in Diverse Times’, which explores young people’s understandings and practices of gender in the UK, is that young people themselves are urgently calling for gender education programmes in schools, colleges and universities. The new Athena Swan Charter represents a potential first step here in its recognition of sex and gender as existing on a spectrum. Athena Swan is a quality charter mark to recognise and award good practices in higher education and research institutions towards the advancement of gender equality. The 2021 Charter moves beyond a gender binary framework to recognise gender as fluid and intersectional. To achieve Athena Swan recognition, HE institutions and departments will now need to evidence that their trans and non-binary students and staff are fully supported at key stages of their education and career. As increasing numbers of young people identify and live beyond or outside the binary of male and female, these developments are crucial to HE’s duty of care to its student and staff populations.

Sara Ahmed’s work, however, is a pertinent reminder of the ways in which the institutionalisation of diversity can work to hamper diversity itself. Her book ‘On Being Included’ (2012) on the institutionalisation of whiteness and racism in HE needs to be read as a what not to do for the EDI practitioner. On their own, then, EDI initiatives are limited and are set to fail if not accompanied by an institutional commitment to social justice. As statistics show (advance-he.ac.uk/knowledge-hub/equality-higher-education-statistical-report-2020) and trans, non-binary and gender non-confirming students and staff keep trying to tell us, the stakes are high in terms of the educational attainment, emotional wellbeing and mental health.

While, in the UK, pushback against the concept of ‘gender’ is most evident in particular feminist perspectives, it is crucial to adopt a broader analysis. As Judith Butler (2021) writes in their recent Guardian piece:

The attacks on so-called “gender ideology” have grown in recent years throughout the world, dominating public debate stoked by electronic networks and backed by extensive rightwing Catholic and evangelical organizations. Although not always in accord, these groups concur that the traditional family is under attack, that children in the classroom are being indoctrinated to become homosexuals, and that “gender” is a dangerous, if not diabolical, ideology threatening to destroy families, local cultures, civilization, and even “man” himself.

Further, as Butler documents, internationally, the war on ‘gender’ has led to a number of alarming policy responses in recent months:

In June, the Hungarian parliament voted overwhelmingly to eliminate from public schools all teaching related to “homosexuality and gender change”, associating LGBTQI rights and education with pedophilia and totalitarian cultural politics. In late May, Danish MPs passed a resolution against “excessive activism” in academic research environments, including gender studies, race theory, postcolonial and immigration studies in their list of culprits. In December 2020, the supreme court in Romania struck down a law that would have forbidden the teaching of “gender identity theory” but the debate there rages on. Trans-free spaces in Poland have been declared by transphobes eager to purify Poland of corrosive cultural influences from the US and the UK. Turkey’s withdrawal from the Istanbul convention in March sent shudders through the EU, since one of its main objections was the inclusion of protections for women and children against violence, and this “problem” was linked to the foreign word, “gender”.

There is, then, very little that is feminist, or, indeed, critcal, about ‘anti-gender’ rhetoric and much vigilance is needed. I suggest that there can be no more room for neutrality. Rather, we must move to adopt a proactive stance against the rise of gender conservatism.

Moving beyond current policy documentation around freedom of speech and duty of care is needed for the development of policy that is fit for purpose for the gender diverse times in which we are all living. Let’s forget, for now, the bullet points in educational policy documentation around duty of care and think instead about the ethic to care. Thinking about what caring means and why it matters – and for whom – holds the potential for EDI to develop beyond a tick list exercise on a strategy document. This can enable it to fully develop as an initiative that has the promise to bring the changes that are needed to secure positive learning and teaching cultures for students and staff from gender marginalised communities. As the slogan goes ‘Trans Rights are Human Rights’. And human rights should, and must, be made to matter.

References

Ahmed, S. (2012) On Being Included: Racism and Diversity in Institutional Life, Duke University Press.

Blumenthal, D. (2014) Little Vast Rooms of Undoing Exploring Identity and Embodiment through Public Toilet Spaces, Rowman and Littlefield.

Butler, J. (2021) ‘Why is the idea of gender provoking backlash the world over?’ The Guardian:https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/commentisfree/2021/oct/23/judith-butler-gender-ideology-backlash

Charles, E. (2019) ‘Decolonizing the Curriculum’, Insights: https://insights.uksg.org/articles/10.1629/uksg.475/

Ditum, S. (2014) ‘No platform’ was once reserved for violent fascists. Now it’s being used to silence debate’. Newstatesman.

Hines, S. (2007) TransForming Gender: Transgender Practices of Identity, Intimacy and Care, Policy Press.

Jones, C. and Slater, J. (2020) ‘The Toilet Debate: Stalling Trans Possibilities and Defending ‘Women’s Protected Spaces’, The Sociological Review, 68:: 4: 834-851.

Lavery, G. (2021) ‘The UK Media Has Seriously Bungled the Kathleen Stock Story’: grace.substack.com

Phipps, A. (2016) ‘Whose Personal is more Political? Experience in Contemporary Feminist Politics’, Feminist Theory, 17: 3: 303-321.

Scott, J. W. (2019) Knowledge, Power, and Academic Freedom, University of Columbia Press.

Serano, J. (2007) Whipping Girl: A Transsexual Woman on Sexism and the Scapegoating of Femininity, Seal Press.

Serano, J. (2013) Excluded: Making Feminist and Queer Movements More Inclusive, Seal Press.

Stonewall () LGBT in Britain: https://www.stonewall.org.uk/lgbt-britain-trans-report

Women’s Human Rights Campaign (2020) Declaration on Women’s Sex-based Rights (2021): https://www.womensdeclaration.com/en/declaration-womens-sex-based-rights-full-text/

YouGov (2020) Where does the British public stand on transgender rights: yougov.co.uk/topics/politics/articles-reports/2020/07/16/where-does-british-public-stand-transgender-rights